Blogging in the 18th century

We think of blogging as a recent phenomenon, like the selfie or screw-top wine bottles, and so no doubt it is. Yet it has its rough equivalent in the 1500-word essays that Dr Johnson turned out twice weekly at the beginning of the 1750s under the general title of The Rambler. Having recently had some trouble with a publisher, I went back to my selection of these because I’d remembered it included pieces with titles such as `Anxieties of Literature’ or, perhaps more pertinently, `Vanity of an Author’s Expectations’. In Jane Austen’s Persuasion, Anne Elliot meets a young man whose fiancé has recently died and is feeding his melancholy with liberal doses of romantic poetry. She ventures to recommend a `larger allowance of prose in his daily study’ from the works of our `best moralists’. Had Austen herself been asked to particularize, as her heroine is, Dr Johnson would have no doubt been one of the first names on her list. Certainly he is a writer who, as Anne Elliot puts it, is able to `rouse and fortify the mind’.

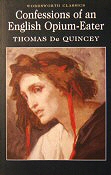

My selection of The Rambler contains about a third of the over two hundred essays Johnson wrote and is an old, hard-backed Everyman edition. These books began appearing in 1906 and catered for a newly emergent public of self-improvers created by educational reform, people like D. H. Lawrence or Jessie Chambers who at that time were burrowing away industriously in the backwater that was Eastwood. Their low cost gave them a function not dissimilar to that of Wordsworth Classics now. On the back of my copy of The Rambler there is list of about sixty of the 500 authors Everyman claimed to have published, together with the general boast of `forty million copies sold’. `No place affords a more striking conviction of the vanity of human hopes than a public library’ Johnson writes, yet most of the names on the author list are still recognizable although what it suggests is that the `common reader’ of the past had a stronger digestion than he or she has now. Between George Eliot and Fielding, for example, there is Euripides, and between Wordsworth and Zola, Xenophon. Only one name is likely to be unfamiliar and that comes at the very beginning where, before Aristotle and Austen, there is `Ainsworth’. Those of us who read English at the university are likely to be able to respond immediately here with `Harrison’, especially if we happened to have done the course on the 19th century novel; and even offer the titles of a couple of Harrison Ainsworth’s works, even if it is doubtful whether there would then be many of us who could go on to describe what happens in any one of them. But then, as Johnson again says, `if we look back over past times we find innumerable names of authors once in high reputation, read perhaps by the beautiful, quoted by the witty, and commended by the grave, but of whom we now know only that they once existed.’

I enjoyed reading through the Rambler selection, whether or not my mind was in a condition to be roused or fortified. Johnson is of course one of Anne Elliot’s `moralists’, and a moralist with what often seem to us antiquated views. Yet he has an acute sense of how unfairly his society treated the female half of the population, noting at one point: `as the faculty of writing has been chiefly a masculine endowment, the reproach of making the world miserable has been always thrown upon the women’. In an essay denouncing the appalling frequency of capital punishment in his day, he points out that `multitudes will be suffered to advance from crime to crime until they deserve death because, if they had been sooner prosecuted, they would have suffered death before they deserved it’. For some readers this will only be a variation in complicated language of the old adage that it is better to be hung for a sheep than a lamb, but for others its neatness has as much appeal as the humane good sense it conveys.

The note most often sounded in Johnson’s essays is pessimistic. `We shall find the vesture of terrestrial existence more heavy and cumbrous the longer it is worn’, he writes at one point, and later in the same essay, `there appears reason to wonder rather that we are preserved so long than that we perish so soon’. Even more chilling is his warning in another piece that `native deformity cannot be rectified, a dear friend cannot return, and the hours of youth trifled away in folly or lost in sickness cannot be restored’. But he understands that there can be a strange kind of pleasure in reading sentences of this variety which is roughly equivalent to what he feels in writing them. In an essay on the death bed as a school of wisdom he talks of someone `swelling with the applause which he has gained by proving that applause is of no value’; and elsewhere he denounces the human screech owls whose only care is to `crush the rising hope, to damp the kindling transport, and allay the golden hours of gaiety with the hateful dross of grief and suspicion’.

I doubt whether many people read The Rambler essays any more. Perhaps, like the millions of blogs that appear every day, they were always destined to be ephemeral. Thanks to Rasselas, the Lives of the Poets, and The Vanity of Human Wishes, but above all thanks to Boswell, Johnson is still a classic; yet a quick glance at the set texts in schools and universities might suggest that in twenty years’ time his name will cause as much puzzlement as `Ainsworth’ does now, especially if, in that intervening period, the title of which he was so proud is dropped by the wayside. Then it might take not merely someone who has read English at the university but who has engaged in post-graduate study to explain, `Ah yes, with the `h’, that must be Samuel and not Ben’, before adding, with some complacency, `unless of course it’s Lionel, the poet who, in Hugh Selwyn Mauberley, Pound describes as having met an inglorious death by falling off his stool in a pub’.