Looking the part.

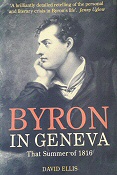

In 1816 Lord Byron turned up in Milan, accompanied by a friend from his university days, John Cam Hobhouse. Their host was a man called di Breme who had been an important official when Lombardy was part of the Napoleonic empire. After a dinner at his home, di Breme took his two visitors to La Scala where he had hired a box for the season and could introduce them to a number of friends. One of these was Henri Beyle, someone who, after having worked for Napoleon, was in the process of trying to launch a literary career (it was only some time later that he would begin to be best known by one of his many pen names, `Stendhal’). Almost the first things Stendhal noticed about Byron was how remarkably good-looking he was. If you wanted to imagine to yourself a great poet, he would write later, this is how he should look, a somewhat poignant remark given that Stendhal always regarded himself as ugly, and once expressed regret at having the features of an Italian butcher.

That Byron was so handsome, in spite of his club foot, is perhaps one of the minor reasons for his phenomenal success. No-one could have better looked the part. Of more recent writers, the one whose photographic portraits correspond best to the sense we take from his work is surely Samuel Beckett. That strongly featured face, with its unusually deep and sculpted lines, would seem to be the consequence of a life-long battle with a penetratingly gloomy view of the world, and of the strenuous efforts that have to be made in order to find an appropriate literary medium in which to express it. W. H. Auden, of course, has even more lines on his face so that the photographs of him tend to suggest the devastation visited on the French countryside by the First World War; but in his case there are also pockets of loose, sagging flesh and the general impression is not therefore, as it is in Beckett’s, of severe self-discipline but rather of letting oneself go, of dissipation.

How common it is to `read into’ the appearance of writers our impressions of their work is finely illustrated by Proust in one of the best-known episodes of A la recherche du temps perdu. Marcel has long been an admirer of Bergotte, a writer he imagines as a `godlike elder’ and a `Bard with snowy locks’. When he is unexpectedly introduced to him at a dinner party, he finds himself opposite `a youngish, uncouth, thickset and myopic little man, with a red nose curled like a snail shell and a goatee beard’, and is cruelly disappointed. All the fine qualities of Bergotte’s writing appear to go up in smoke along with the image which Marcel had previously harboured of him. Yet as they begin to talk, and Marcel listens to Bergotte’s conversation, he is gradually able to re-associate the work he so much admires with the man he sees in front of him.

I can remember alluding to this ability we have when, in the days when Matthew Arnold was still a name that mattered, a friend was preparing an edition of Culture and Anarchy. He was outraged at one point on being sent by his publisher a portrait for the cover which depicted not Arnold but John Stuart Mill. I tried to comfort him by pointing out that one Victorian with sideburns looked very much like another, and that when the true believer is gazing at the bones of a saint (my friend was a Catholic), it doesn’t much matter if these have in fact been recently picked up from the local charnel house. Yet I could see he might have been right to insist on the value of authenticity when I thought about Shakespeare. There are only two portraits of Shakespeare which are authentic in the sense that they must have been commissioned by people who knew what he looked like. The first is the engraving in the First Folio. This is the work of either the Flemish engraver Martin Droeshout or his uncle of the same name, and is almost certainly copied from a painted portrait. That there were such things is evident from what are known as the `Parnassus plays’, three satirical vehicles written by and for Cambridge students and performed in St. John’s college on various occasions between 1598 and 1603. At one moment during the second of these – the first part of The Return from Parnassus – a foolish and boastful character called Gullio cries out, `Oh sweet Mr Shakespeare, I’ll have his picture in my study at court’. But if Droeshout was indeed working from a picture like the one Gullio mentions, one is tempted to say it cannot have been a very good, although this is a hazardous statement given the patent technical deficiencies of the engraving. It does not take much expertise, for example, to notice how the over-sized head is grotesquely separated from the puny shoulders, rather like, as Samuel Schoenbaum memorably puts it, `the decapitated Baptist being served up to Salome’ on a lace collar. The man Droeshout depicted is bald, and so too is the second authentic portrait, the half-length, life-size bust of Shakespeare which is set back in a niche in Stratford parish church and flanked by miniature Corinthian pillars. This depicts its subject writing and with his mouth slightly open so that, to borrow Schoenbaum’s words again, it seems as if Shakespeare is either `declaiming his newly minted verses’, or gawping `in the throes of creation’. It was probably the work of Gheerhart Janssen the younger, a sculptor of Dutch descent who operated out of Southwark. It is not easy to recognise these two images as representations of the same person, even at different stages of his life. If one puts aside the notion that Droeshout was simply a bad artist, for example, one would have to say that in his final years Shakespeare developed shoulders he had never had before, and that also the hydrocephalus which, on the strength of the massive forehead in the engraving, some commentators have attributed to him, had been miraculously cured.

These two `authentic’ depictions of our greatest writer have been found very disappointing — `like a self-satisfied pork butcher’ is how a well-known critic once described the Shakespeare of the bust, in a manifestation of that same, strange prejudice against the butchering trade Stendhal exhibits. The disappointment is why an unconvincing case is made from time to time for some recently unearthed portrait of an anonymous gentleman that might be thought to show the Bard in a more favourable light. But the real solution to the difficulties the bust and engraving present is offered by Shakespeare himself. In the fourth scene of Macbeth, Duncan is clearly puzzled by his failure to have recognised in the former Thane of Cawdor a potential traitor and decides `There’s no art / To find the mind’s construction in the face’, a crucial truth which would have been confirmed for him very quickly, had he been able to survive the confirmation.